What Is Consciousness?

And how should we think about whether we want AI systems to have it?

About This Blog

Welcome to the first post of this blog, written to provide a new take on some of today’s popular questions: What kinds of intelligent systems should be built? How should we build them to avoid unpleasant surprises? What kinds of useful analogies can we draw between natural intelligence, artificial intelligence of today, and the wilder stuff that may be just over the horizon?

The particular take I’ll share draws on my background in developing better tools for programmers, both as a professor of computer science at MIT and in connection to a number of commercial companies over the years. My even narrower specialty is formal methods, where we do machine-checked mathematical proofs that programs are correct. We’ll see that the mindset behind building reliable computer systems generalizes to broader scopes that include big-picture societal questions. I expect most readers will find the perspective of this blog to be a strange mix of (1) software-engineering team meeting and (2) late-night discussion by a bunch of college kids on the meaning of life. What differentiates those two established styles of communication will even be a topic we cover explicitly.

I’m using the blog as a chance to “think in public” about ideas that may come together in book form eventually. To that end, feedback is especially appreciated on which explanations and arguments work and which fall flat.

As we think about designing artificial intelligences, it’s natural to copy human intelligence by default. One of my main themes in this blog is going to be identifying design choices where we have the most reason to diverge from intuitive defaults (whether they come from introspecting about our own intelligence or from other sources). The first question I’ll start with is should/can we build artificial intelligences to be conscious? I chose this one to require the least lead-up to be able to tackle properly, though we’ll see it also has the complication that, in the end, I conclude it’s something of a trick question. The take I’ll present is closely connected to a variety of ideas in cognitive science like around theory of mind, but their details won’t be so important for the conclusion I draw. To work up to a good answer to the question of consciousness, we should start by reviewing some more-primitive artificial “minds.”

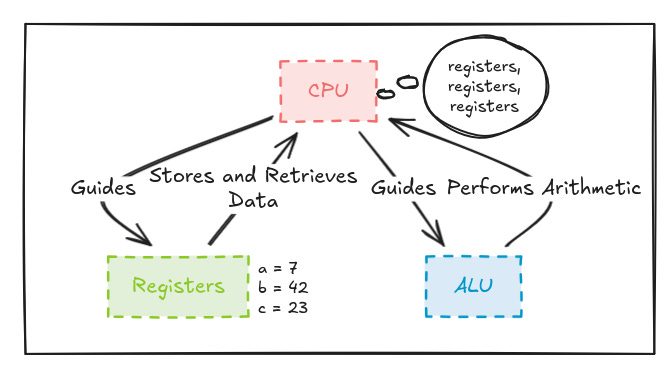

Programmable Hardware

The classic general-purpose computer that we’re used to is the CPU (central processing unit). One of its central ideas is registers, named slots that hold numbers. The programs that run on CPUs request sequences of simple operations, which can include grabbing the values from two registers, adding them together, and stashing the result in another register. An ALU (arithmetic-logic unit) handles the actual arithmetic.

If we start anthropomorphizing the CPU, it’s natural to imagine its thoughts being full of registers. CPUs as we know them can’t compute much that’s very interesting without using registers.

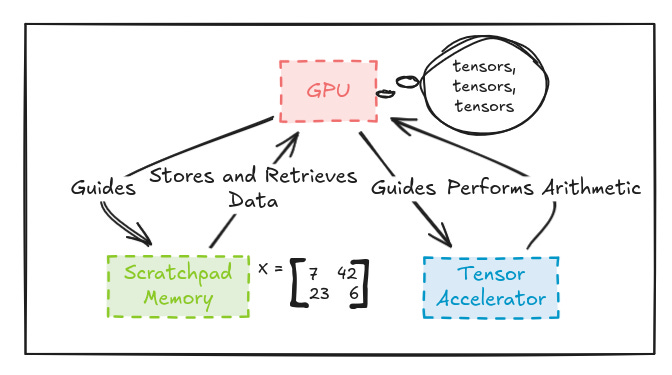

Another important kind of hardware today is the GPU (graphics processing unit). The name is something of a misnomer today, since what puts GPUs in the news is use for AI (more specifically deep learning), not graphics.

For many important workloads, GPUs provide better performance by allowing computation to happen on many numbers at once, which is harder to do nicely on CPUs. Deep learning is described in terms of operations on tensors, structures that can contain many numbers. As a result, the highest-performance GPUs have been given hardware specialized to tensor operations, allowing them to be performed more quickly. Now we can say that, like CPUs are naturally obsessed with registers, GPUs have tensors on the mind.

Programs and Interpreters

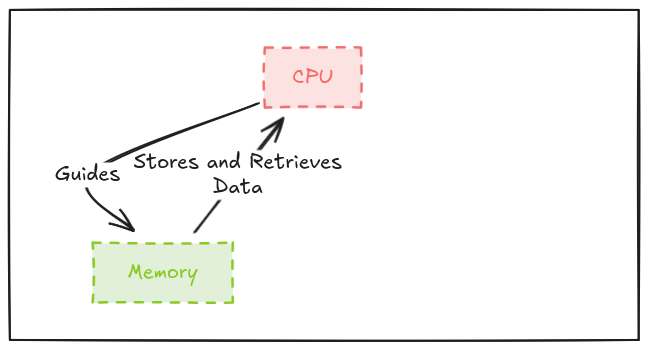

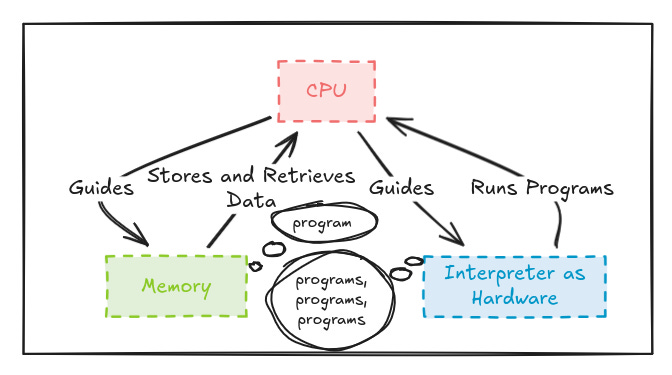

Our little sketches haven’t accounted for the fact that CPUs and GPUs are examples of von Neumann architectures. In other words, they feature unified memory that can contain both the obvious stuff like data (e.g. tensors we want to multiply) but also code, the very programs that we are running. Each such piece of hardware tends to have a native language (like machine code) that it can execute directly. However, it is often useful to execute other languages, for reasons including that high-level languages like Python are much easier than machine languages for humans to write. How can we teach the CPU a new language?

The trick is to write an interpreter, a program that can execute programs in some language. Now we can, say, load into the unified memory of a CPU both a Python program and a Python interpreter, the latter written in the CPU’s native language. (In reality, the picture could be more complicated, with a complex bootstrapping process where the interpreter might itself be written in a nonnative language.)

It’s a triumph of human ingenuity that we figured out how to build one piece of hardware that can be taught successively more-complex languages, in effect by explaining each one in terms of those that came before. However, all of those layers of interpretation can get costly, slowing down execution and requiring more memory. One solution close to my heart is compilation, where we use automatic translation of other languages into machine languages. But what should we do when some language is really interestingly different from the CPU’s native language, where, say, performance still isn’t good enough in machine language? We already saw an example of a fix above, where GPUs started to grow specialized tensor hardware, which speak a simple language of programs. More generally, we can add interpreters in hardware.

The new language spoken by our hardware interpreter is far from fundamental to computing. In fact, we probably came up with it through an explicit design process. Yet if we again anthropomorphize the hardware interpreter, we imagine it thinking of its kind of program as very real indeed. It wants to chat about those programs like we humans bring up the weather in small talk.

Now we have the tools to return to the problem of consciousness.

Part of Your Brain is an Interpreter for (Models of) Other Brains

In a world full of thinking agents, it’s extremely useful for an agent to understand what the others are thinking. It’s so useful that the stingy evolutionary process invested in special hardware for that understanding. Whether to predict the thoughts of animals you’re hunting or the other hunters you’ve teamed up with, there is a large payoff for survival and reproduction.

I should be clear at this point that science overall has far from complete understanding of how the human brain works, and I personally have even less of an understanding, never having studied neuroscience, but I’m told that there is now good evidence that the right temporoparietal junction and superior temporal sulcus in particular include brain hardware aiding social interaction.

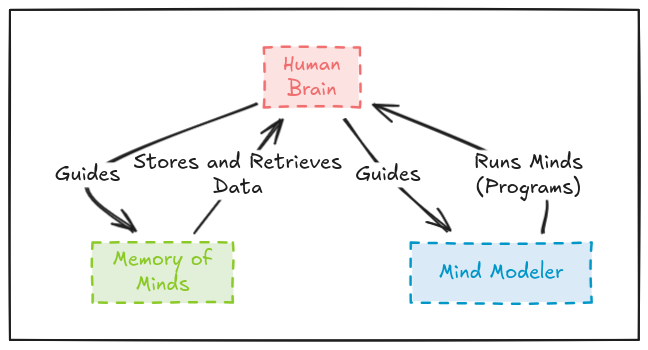

So it seems that our brains contain special circuitry for running models of other minds. We could be dealing with what is effectively an interpreter for a programming language that covers the scope of other minds we might want to model. Descriptions of the minds we’re tracking may be stored in general-purpose memory, as on a CPU, or they might be in memory more-specialized to the task. When needed, we would load mind descriptions out of memory and run them through the specialized interpreter in hardware, to predict decisions by the real minds we model.

So then what is consciousness? I would argue it’s a trick question! There is no objective idea of consciousness that can be defended from first principles. The reality is more like how two CPUs having a nice chat would be perfectly comfortable talking about registers. They both know exactly what they’re talking about, at the same time as registers have no fundamental reality in the world. Humans discussing consciousness are referring to some combination of a programming language and an interpreter for it built into their brains, even if most aren’t at all prepared to use that terminology.

By the way, a number of other common words and phrases seem to mean essentially the same thing. A good example is “free will.” Our brains use it to refer to other agents that can be persuaded to act differently, and such persuasion is clearly a useful tool for survival. However, the concept comes down to methods for understanding certain kinds of programs (within other minds) and is no more fundamental than the tools of the trade for diagnosing bugs in Python programs.

The Upshot for Artificial Intelligence

I would claim that it’s hard to talk productively about consciousness without confronting these questions of what is built into our human brains and how we perceive other minds. Does a philosophical zombie, which behaves like a human in all outward ways, have true consciousness? There’s already a tradition of answering “yes,” for instance by Daniel Dennett in Consciousness Explained. I’m just using this example as an introduction to the general game I’ll be playing, presenting such questions from the hardnosed perspective of a software-engineering team, so we can think similarly about all levels of this design challenge (“what kinds of artificial intelligence should we build?”). Our brains also have special circuitry for recognizing the taste of umami, but we don’t consider it respectable to build learned philosophy on umami – it’s obviously too arbitrary and evolutionarily contingent. (At least, that’s my own intuitive position, where the qualia that philosophers love discussing have always struck me as really referencing human mental circuitry and nothing more fundamental.)

There’s one big fundamental problem for trying to apply our intuitions about consciousness to artificial intelligence. Evolution moves slowly. Anatomically modern humans appeared only hundreds of thousands of years ago, and relatively little evolution has happened in the mean time. Fundamentally, evolution is stingy in developing new mechanisms, because it takes so much work to find them through random search. As a result, there is very little diversity of minds in the natural world. Many brains share a common lineage from initial “discoveries” of brain types by evolution. There may also have been parallel evolution of different cognitive styles that are relatively easy to find by trial and error.

The point is that a relatively unified programming language suffices for modeling the minds that we encounter, and we benefit from our hardware interpreter specialized to that language, but we are about to see a flowering of kinds of artificial intelligence that will not fit that language well. The future is a lot weirder than our intuitions prepare us for! Should future intelligences be denied rights just because they’re written in the wrong programming language? I would say “no,” arriving at our conclusion where we see the question should/can we build artificial intelligences to be conscious? as a trick question. The question is a sort of cognitive illusion that we should put aside.

It was convenient for me to start with this question because it doesn’t take much explanation to set up the claim I want to make. The engineering implications of the position are a little murky, not obviously pushing us toward specific design choices. However, my next post will cover another position that suggests specific design strategies that I haven’t seen discussed elsewhere. We are going to follow a gradual path toward advice for designing intelligent systems with strong mathematical guarantees of compatibility with our values, and many of the design choices I suggest will be pretty different from mainstream ideas. Along the way, I’ll expand on many of the topics covered offhandedly above, including design of efficient hardware and software, evolution and how it got us here, and most importantly which evolved elements we should keep and which we should discard in designing our own efficient decision-making systems.

Sharp analogy. The interpreter framing cuts through alot of philosophical fog by grounding consciousness in actual cognitive architcture rather than abstraction. What I find interesting is how this suggests the diversity crisis, that we're about to encounter minds that dont fit our modeling language at all. Kind of forces the question of whether rights should depend on compatibility with human brain architecture or something more fundamental.

Adam, in terms of the mind modeler being useful to run models of "other" minds, do you consider it possible/important that the mind modeler also allows us to introspect on the "thinking" of our own minds. The experience of introspection seems to lead to the experience (perhaps illusory) of our own consciousness. (I am reminded of Brian Smith's 3-lisp)